Turning failure into a strategic weapon has become one of the most powerful attributes of successful entrepreneurs who, rather than dreading setbacks, have learned to embrace them as a valuable part of the innovation process.

The value of failing fast and cheaply is a philosophy many people in our success-obsessed corporate culture find challenging. Still, it’s a philosophy quickly becoming ingrained in modern MBA students and the enterprises they create and manage.

The ‘fail fast’ philosophy values extensive testing and incremental development to determine whether an idea has value. An important goal of the philosophy is to cut losses when testing reveals something isn’t working and quickly try something else, a concept known as pivoting.

It’s a philosophy that The University of Queensland (UQ) MBA graduate Richard McDougall put to good practice when helping to build to create funds management business Hamilton12.

Hamilton12 started six years ago after Richard became disillusioned with his career in investment banking and decided to try something new.

With his UQ MBA (2015) under his belt and an extensive network of contacts created during his studies, Richard teamed up with fellow UQ MBA graduate Damian Vassallo to start the business with a plan to offer robo-advice to Self Managed Super Fund (SMSF) trustees.

“It was a great idea that failed the first test,” he said. “We went to the market and tested demand from trustees, and for various reasons, there simply wasn’t enough interest.”

“Despite putting a fair bit of time but not much money into it, we moved on with the knowledge that we had gained about the SMSF sector and its needs. For example, we realised that many of these SMSFs were steering their investments to passive funds, but from an after-tax, income-enhancing perspective, that doesn’t really make sense.”

Through their ongoing relationship with the UQ Business School, the pair eventually teamed up with former UQ finance lecturer and imputation credit expert Dr Jason Hall to create a custom share market index for S&P — the Hamilton12 Australian Diversified Yield Daily Index (Superannuation).

“By default, we had created a new investment benchmark, and while it wasn’t a failure, we still didn’t have a lasting business with growth potential,” Richard said.

“We were approached by a couple of ETF (Exchange Traded Funds) managers to create a product that tracked the index that we created, but ultimately decided to go down the path of creating our own fund and this year launched the Hamilton12 Australian Shares Income Fund.”

“It has been a long journey with many twists and turns. We always knew we were on to something but just had to be prepared to cut our losses and use our learnings to push the business forward.”

UQ Business School Lecturer in Innovation and Entrepreneurship Dr Sarel Gronum said successful entrepreneurs like Richard not only use failure differently but view it differently.

“Entrepreneurs view failure not as the opposite of success, but rather, the opposite of mediocrity,” he said. “They use failure as part of the experimentation process to shape outcomes by providing valuable learning that directs action.”

The caveat is that you should maximise learning by creatively devising experiments that allow you to “fail fast, often, and cheap.”

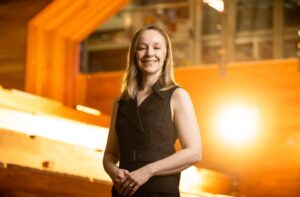

Anne-Marie Birkill (pictured) is the co-founder, Venture Partner, and executive director at venture capital and venture credit firm OneVentures. For her, the “fail early, fail often but always fail forward” culture is an essential feature of successful start-ups.

“Taking calculated risks, understanding the outcomes and then iterating your business to improve will always shorten the path to high-value innovations and inventions,” she said.

As a venture capitalist, Anne-Marie, who graduated with an MBA from UQ in 2002, sees the inner workings of dozens of start-ups across the OneVentures portfolio and believes that corporate culture is critical to the success of an iterative learning process.

“You need a strong culture that allows people to experiment,” she said. “Sometimes you have to take one step back to take two steps forward, but ensuring the process is robust and transparent will always lead to better outcomes.”

“In technology and healthcare investing, you’re always in an experimental process. If you take the clinical trials process, for example, it’s very difficult to see what is going to happen, and there’s a universe of possibilities out there, so you need to be prepared to embrace setbacks.”

Anne-Marie credits her MBA for helping her develop a deeper understanding of the value of failure beyond the superficial relationship between cause and effect.

“As an MBA candidate, you learn to consider the impact of events and decisions across the entire organisation, not just the narrow lens, so when things go wrong, you can understand the opportunity for the business, not just the threat.”

How can businesses incorporate ‘failing fast’ strategies and techniques into their everyday operations?

Teaching into the UQ MBA, Dr Gronum integrates the concept of ‘failing fast’ across a range of learning experiences and believes there are several ways businesses can benefit from the concept.

- Allow employees the opportunity to try new things that have less certain outcomes. A risk-averse culture where failure isn’t tolerated will lead to small incremental innovations that may increase efficiencies but will not enhance future earning potential.

- Build KPIs into performance appraisal systems where unsuccessful endeavours are also recorded and recognised. Current performance appraisals only value successes and largely negate the multiple failures that led to these successes.

- Adopt a portfolio approach to innovations with a good mix of incremental innovations and potential radical innovations. The more opportunities you create to fail, the more opportunities you create to learn and succeed.

Learn advanced business innovation and strategy skills to succeed in your career with a UQ MBA.